Munich, 23 July 2024 – Despite global efforts to end HIV and AIDS, the epidemic has been persistent. In 2022, 1.3 million people were newly infected with a new HIV infection every 24 seconds. New infections continue to rise among key populations, and in some middle-income countries (MICs). Unfortunately, MICs – particularly the upper middle-income countries in different regions like Thailand, Morocco, Brazil have been consistently excluded from voluntary licensing agreements that open up price lowering generic competition, and must pay unaffordable prices demanded by the pharmaceutical corporations and end up rationing the medicines essential for treatment and prevention. “Biomedical advances are not going to end HIV unless everyone has access to them,” says Solange Baptiste, Executive Director of ITPC Global that leads the Make Medicines Affordable Campaign. “The problem is that pharma has monopoly control over supply and pricing on newer therapeutics. Preventing access to affordable generic medicines in MICs shifts the problem – instead of solving it. While governments could use compulsory measures, like refusing any evergreening patent applications to be granted or issuing compulsory license on lenacapavir to ensure full access to it for people in need.”

Impressive results from an HIV prevention trial of lenacapavir (LEN) call for a global access plan. The PURPOSE-1 trial compared oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) versus long-acting, twice-yearly injections of LEN in adolescent girls and young women in South Africa and Uganda. PURPOSE-1 was stopped early, because LEN was significantly more effective than oral PrEP: there were zero new HIV infections among the 2,134 participants who received twice-yearly injections of LEN, versus 1.7% among 1,068 participants who received tenofovir/emtricitabine and 2% among 2,136 participants.

Currently, LEN is approved in high-income countries as part of treatment for people with multidrug-resistant HIV. In the United States, it is priced at over $40,000 per person, per year. Other LEN prevention trials are ongoing, with results expected in late 2024 or 2025; if they are consistent with PURPOSE-1, it is likely to be approved.

Gilead, who has applied for patents across LMICs, including key manufacturing countries, has announced plans for a bilateral voluntary license (VL), and temporary price reductions for LEN, but they have not disclosed which countries that will be included in the VL, or access pricing for LEN. Researchers from Liverpool University have estimated that generic LEN could be profitably mass-produced at affordable prices, initially at $63- $93 per person, per year, and falling to $26- $40 per person, per year when volume reaches 10 million.

Within Make Medicines Affordable Campaign HIV community-based organizations is now challenging Gilead’s patent applications in various LMICs (Fundacion GEP in Argentina, DNP+ in India, TNP+ in Thailand, VNP+ in Vietnam). They already filed at least 8 patent oppositions to ensure early entry of independent manufacturers of generic version of this medicine.

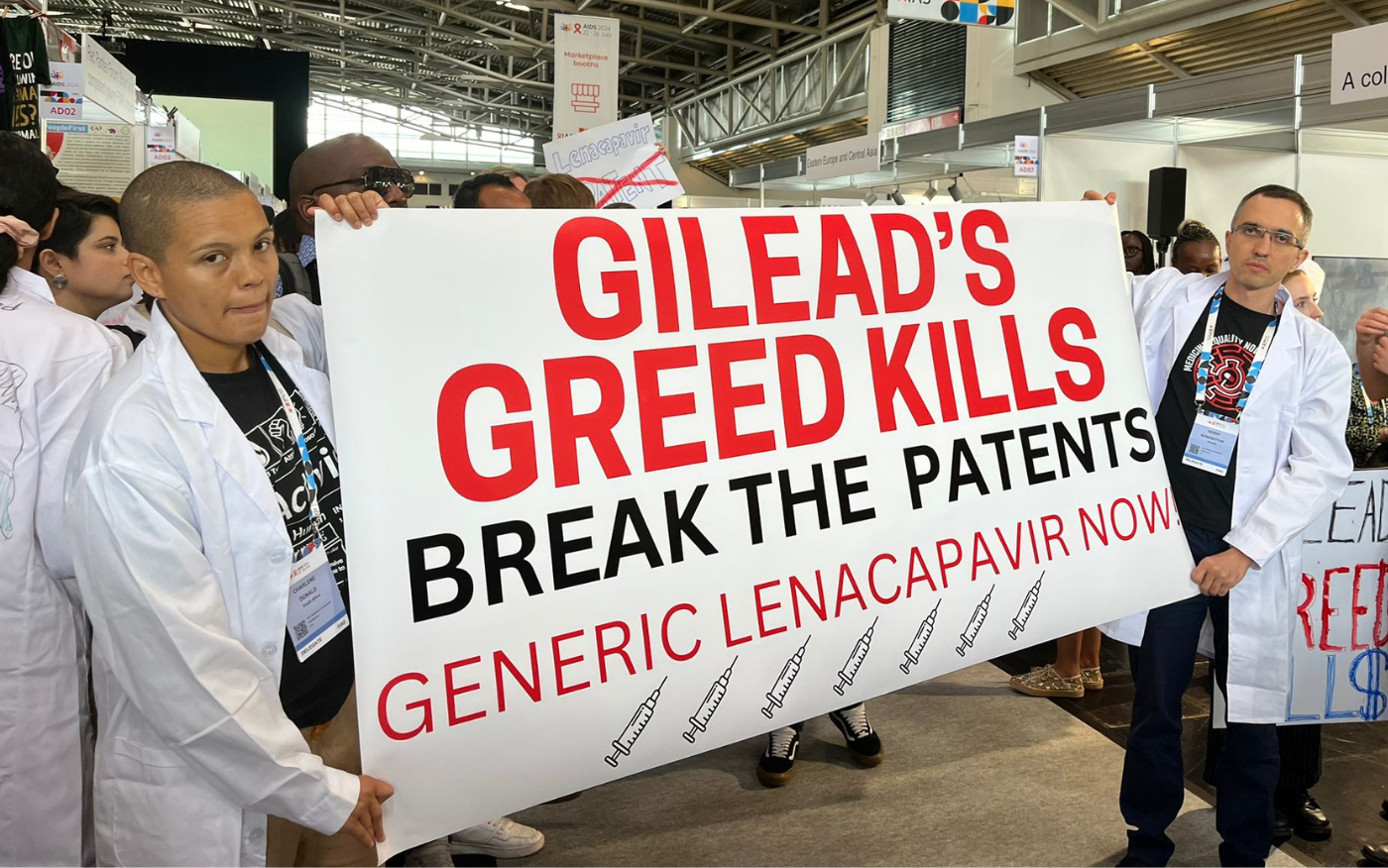

“Lenacapavir is 100% effective–there must be 100% access,” said Asia Russell of Health GAP. “Gilead’s monopoly must not obstruct generic competition, and countries must act now to produce generic versions of this potentially pandemic defeating prevention tool. No one should be forced to accept inferior prevention options because of Gilead’s greed.”

“To encourage access to Lenacapavir, all conditions blocking and delaying R&D, drug registration, and supply of generic Lenacapavir should be removed out of the upcoming voluntary license, including the control over API supply and high royalty fee.’ Suggests Charmsak Kittitrakul from Thai Network of People Living with HIV (TNP+), – ‘There must be no restrictions preventing generic manufacturers to supply Lenacapavir to the countries that are excluded from the upcoming voluntary license and governments should issue compulsory licenses or make use of other TRIPs flexibility measures, if patents are granted. Thailand should start producing generic version of the drug, to avoid the delay in access for people living with HIV or to key population.’

“In Brazil we are an extremely unequal country with a high HIV incidence. We should not be excluded from access to superior HIV prevention technologies like lenacapavir. Our public health system, which serves 200 million people and 1 million people living with HIV, should not be forced to pay Gilead’s prohibitively high price for this HIV medicine. – says Susana Van Der Ploeg from ABIA/GTPI, Brazil – ‘We have legal mechanisms to guarantee access and safeguard people’s lives including compulsory licensing. This should be used to prevent abuse of the patent system and defend people’s lives before profit. That’s what we call ‘putting people first.”

LEN has the potential to become transformative – but greed may prevent it from being able to do so. “Why should a for-profit company be in charge of people’s health?” asks Othman Mellouk, Access to Diagnostics and Medicines Lead, Morocco, – “the price of such an important medicines should be based on cost of manufacturing as Andrew Hill study demonstrated and not be fuelled by big pharma greed.”