In 2006, Parina Subba founded an organisation named Dristi (meaning ‘vision’ in Nepali). Dristi’s motto is, simply: ‘Rights to existence’. It is an activist group of women who use drugs and live with HIV working towards the most elemental, and elusive, goals in health and human rights.

Parina begins every morning exercising in the yard outside the house she has made into a place of safety for women who use drugs, live with HIV, and sell sex in Nepal’s capital city, Kathmandu. Parina’s interval training helps to prepare her for what lies ahead each day: the obstacle course of lockdown. She must navigate the terrain of COVID-infection control and movement restrictions, while scaling up access to essential medicines and food supplies.

Figure 1: Parina Subba of Dristi Nepal during a morning exercise session, June 2020.

Parina has an intimate understanding of endurance. She knows, first-hand, about the transformative potential of a crisis: ‘I have been through tough situations where I’ve faced lots of problems. I’ve experienced discrimination because of my gender and my caste… I didn’t choose to became an activist, I just became one. I don’t ‘do’ injustice, wherever, to whomever it is.’

Parina explains: ‘I’ve been doing this kind of work for the last fifteen, sixteen years. There’s still a lot more to do, especially on gender equality. There are some changes in understanding the role of women in our society. But women who are outspoken, like me, who fight for rights, we are accused of just going crazy. It’s considered to be bad, to question a women’s role in society.’

When COVID-19 emerged, Dristi was working with women to support their health and wellbeing in ways that resonated with their experiences. Parina explained: ‘We work with women, and what we do with them depends on their needs. If they are sex workers, and if they are working in different places, we work through our wider networks, across different valleys to connect people to support. This means that we are many different things for different people: some need access to HIV medicine, some are surviving violence, some are migrant workers and have problems with citizenship, some need education, or advice or how to leave abusive partners.’

The women who are part of Dristi’s community of care experience intricate overlays of stigma. Some are sex workers, some use drugs, and some live with HIV. In Nepal, hierarchies of gender, class and caste designate these women as among the most marginalised demographic groups. They bear the brunt of their vulnerabilities in part through shouldering heavier burdens of disease and death.

While Nepal has made significant progress in recent years in key health and development indicators, it ranks 147th of 189 countries assessed according to the United Nations Human Development Index. A 2019 report by the United Nations Development Program captures the gendered disparities in health, education and control over economic resources in Nepal. Women have fewer years of schooling, higher rates of illiteracy, and weaker control over economic resources (such as land) than men.

The COVID-19 pandemic in Nepal has highlighted and deepened existing inequalities in access to essential health services and the protection of human rights among women with HIV, migrants, and other vulnerable populations. It is a major challenge for civil society organisations to continue to support their communities of care, while engaging critically with the state to ensure accountability and transparency.

In April 2020, the Nepal published its COVID-19 ‘Preparedness and Response Plan’. The plan outlined Nepal’s national outbreak response, and provided extensive and ambitious commitments to the COVID-19 pandemic. A month later, Parina vented her frustration about the state’s failures to deliver its promises: ‘Everything is there on paper, but nothing seems to be happening.’

In the absence of public access to COVID-testing, and in the midst of a lockdown which vapourised the income of casual or ‘daily wages’ workers, Dristi has done what it knows best: flexing and stretching the muscles that have been strengthened over decades of work in health and human rights. In collaboration with partners in civil society, Dristi evolved, revealing the strengths of activists in responding rapidly and effectively to the changing needs of their communities.

Parina and her colleagues worked through networks of health activists to secure government permits for essential workers to deliver essential medicines and support to women living in Kathmandu, as well as those who had left the city and returned to their homes in more rural areas to wait-out the lockdown. They also dedicated precious organisational resources to buying personal protective equipment to ensure that staff could continue to provide essential services while maintaining infection control and, of course, abiding by social distancing regulations.

Since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in Nepal, Dristi’s support has either been offered remotely, using digital platforms or – for those women without smart phones or internet access – through direct outreach with protective equipment and social distancing measures in place.

Parina is witnessing the real-world impacts of COVID-19 in Nepal, not just in terms of continued access to essential medicines, but in relation to hunger and violence among Dristi’s community of care. These effects – of greater food and income insecurity – are particularly strong among women whose work is in the ‘informal economy’, including through sex work, and who have lost their livelihoods due to lockdown restrictions on movement, and on tourism and the entertainment industries.

Parina recounts: ‘We heard about COVID-19 around February 2020. When it first started happening, we asked ourselves: “What is it? Why is it coming? From where it’s coming”? There wasn’t reliable information out there. We were confused. A few countries were already “locked down”, but Nepal didn’t have any infrastructure in place and didn’t provide public access to how it was going to respond. I was scared.’

Since the first notified cases of COVID-19 in Nepal, in April 2020, Dristi has mobilised rapidly and effectively to promote public health (through prevention and management of COVID-19), to maintain and strengthen existing essential health services, and to hold its government accountable for its commitments to delivering an effective COVID-19 response.

Dristi worked furiously to prepare for what the coming COVID-pandemic had in store for Nepal. Parina explained:

‘Just before the Just before the lockdown was announced in Nepal, we were extremely busy. We held a lot of meetings, and managed to get hold of women to make new plans for continuing to provide our services, to support them.

We had to explore how to support women remotely, to come up with a strategy on how to retain them in services. Whatever we did in the field, we wore masks and gloves.’

Assessing risks and continuing to provide women with essential health and support services are part of a careful calculation, which Dristi makes – in collaboration with colleagues – working from the latest available evidence. Keeping up with the scientific developments in COVID-research is another task, balanced in relation to copious other responsibilities.

‘As the leader of this organisation’, Parina explained, ‘I face a challenge. I don’t want my team to take risks, but I also have to keep supporting people. Providing ART, that’s not our only responsibility. We have responsibilities to the women we support, to ensure that they have food, that their kids have food, and that they are in a safe place.

Some women have gone back to their villages, and now they can’t escape. Hunger is a huge concern of ours, because we cannot neglect food if we want people to take ART. You cannot give people medicines if they don’t have food to eat. Dristi as an organisation, it’s not just about ART, and our response to the COVID-19 pandemic has not just been about securing access to ART. It has also been about sexual and reproductive health support, and food security. This is about health activism and human rights, it’s not just about HIV treatment. Now is the time for us to come out of the “box” of HIV. We have to address the other issues that are important to the people we work with.’

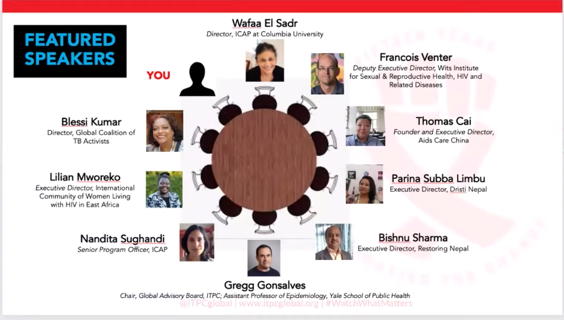

Providing emergency medicines and food aid have been cornerstones of Dristi’s COVID-19 response. But, as the pandemic takes root, Parina has identified ‘government accountability’ as the ‘first priority’ in Dristi’s work, in collaboration with the International Treatment Preparedness Coalition.

As with every facet of healthcare provision, the COVID-19 pandemic presents new challenges in access and adherence to essential healthcare for HIV and TB. However, a lack of data on how key populations are understanding, and responding to, the COVID-19 pandemic, means that rapidly-emerging healthcare responses – locally, nationally and globally – fail to incorporate the real-world experiences of citizens.

To ensure that these voices are heard, ITPC and Dristi are conducting a rapid assessment of the COVID-19 and its impacts on other essential health services and human rights. A community monitoring tool has been developed collaboratively, and is currently being implemented with the women that Dristi supports. This monitoring tool empowers local women to assess the provision of essential services, and to identify urgent needs to be addressed by government, in partnership with civil society and others.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed critical inequities in global health provision. It has also emphasised the power and effectiveness of community-based, activist organisations in confronting and managing public health crises, drawing deeply on their inlaid experience of responding to and treating diseases, and of promoting health and human rights.

Dristi Nepal’s ability to mount an agile and empowered response to COVID-19 has flourished, in part, because of its activist past. In the current era of this new pandemic, past and present responses will define the future.